An ongoing discussion of how the comics provide prequels, sequels, and tie-ins to the Star Trek episodes and films, soon to be a book from BearManor Media. Click here to view an archive of this article series.

108: IDW Publishing, 2014

For the most part, IDW has shied away from adaptations in its Star Trek lineup, aside from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the episode “Balance of Terror,” the 2009 film, and the re-imagined episodes set in the Kelvin timeline. When the publisher adapted “The City on the Edge of Forever,” often hailed as The Original Series’ finest hour, it did more than merely regurgitating what fans had already seen. This week, we’ll examine Star Trek: Harlan Ellison’s The City on the Edge of Forever—The Original Teleplay.

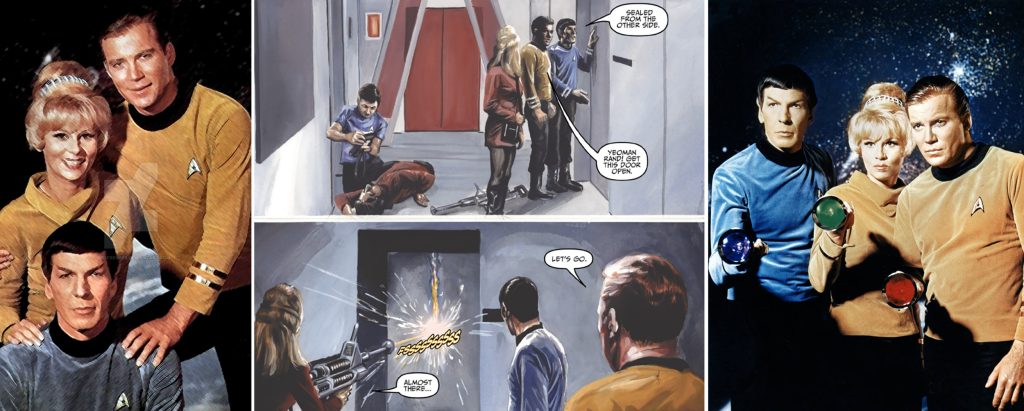

The miniseries was penned by Scott and David Tipton, with interior artwork by James Kenneth Woodward and covers from Juan Ortiz—whose hardcover art books based on Star Trek and The Next Generation are must-haves—as well as Paul Shipper. The comic adapts Ellison’s script, from before Gene Roddenberry, Dorothy Fontana, and others made major changes he’d vehemently opposed. Various drafts have been published by Pocket Books, Borderlands Press, White Wolf Publishing, and Open Road Media, but this was the first time readers saw the story play out visually.

The teleplay was conceived early in the show’s development, and its evolution proved tumultuous, damaging the novelist’s relationship with Roddenberry and Paramount. Although it was the 28th episode aired, “The City on the Edge of Forever” was assigned in March 1966, with multiple outlines and teleplays produced before the show had even debuted. As such, the producers had not yet fully cemented the program’s premise, so Ellison had little to work with in terms of aligning his writing with other episodes being planned—because he hadn’t seen them.

This is why Spock’s dialogue is uncharacteristically emotional and personally revealing (he admits to sexual liaisons with women at numerous ports and pleasure planets, for instance, hilariously commenting “I am a Vulcan, Captain, not a neuter.”), and why he directs frequent sarcasm at Jim Kirk, arguing with decisions and deeming humans “barbarians.” It’s why Vulcan is noted to have attained space travel two centuries after Earth, despite the ancient Romulan-Vulcan schism mentioned in “Balance of Terror” (not to mention the events of Star Trek: First Contact), and why the comic is set in the 25th century.

It’s also why Janice Rand has a more active role in the teleplay and comic than she did onscreen, as early marketing materials for the show had indicated she, Spock, and Kirk would be the main stars. She even wields a phaser rifle, recalling a photo of actor Grace Lee Whitney doing just that. Rand is presented as a highly competent crewmember who can hold her own in a firefight, whereas on TV she was relegated to being “that beautiful yeoman” who fetched coffee, made Kirk feel squirmy, and pouted at her inability to draw his male gaze to her legs, while driving teenage telekinetics crazy.

There are other differences as well. Leonard McCoy doesn’t overdose on cordrazine like he did on television—in fact, the doctor is entirely absent from the story. Montgomery Scott is also nowhere to be seen, despite Roddenberry having infamously told fans that Ellison’s script had depicted Scotty dealing drugs (an inaccuracy that had played a large role in the outspoken writer’s lifelong grudge against Star Trek’s creator).

In McCoy’s place is murderous Richard Beckwith, who sells addictive “dream-narcotics” to others in the crew, giving them song-filled hallucinations so insane an LSD trip would seem tame by comparison. He kills addicted (and similarly surnamed) shipmate LeBeque, and it’s Beckwith who jumps back in time, not Bones. In so doing, the drug dealer prevents Edith Keeler’s death, altering the future for the worse. In the resultant timeline, the Enterprise is now a pirate ship called the Condor, and Spock and Kirk barely escape execution.

The major story beats in the past mostly play out the same: the duo find menial jobs, they wait for their quarry to arrive so they can undo any temporal tampering, and Kirk falls in love with a social worker fated to die. But there are differences in the details. A fearful mob nearly kills Spock for being a “foreigner,” and he silently endures anti-Asian bigotry from several people. What’s more, Kirk hires legless veteran Trooper, fittingly drawn with Ellison’s likeness, to help him find Beckwith. On TV, Trooper was replaced with Rodent, a more generic, one-dimensional transient character. Instead of Rodent accidentally killing himself, Beckwith shoots the World War I vet.

The greatest change involves the method of time travel. In the script and comic, the Guardians (plural) of Forever are not a large stone portal but six spectral giants who protect the timeline from an ancient mountaintop city. For readers unaware of the script’s rocky path to broadcast, the depiction of the vortex may be jarring, and they might find themselves thinking, “That’s not right. There’s only one Guardian and it’s a big rock named Carl. Who is this Beckwith guy? And where the heck is McCoy?”

The thing to remember, when it comes to Beckwith, LeBeque, the narcotics angle, Spock’s emotional outbursts and sexual history, the humanoid Guardians of Forever, and other stark differences, is that it’s not meant to be consistent with the episode. The comic provides a rare glimpse into what might have been—a look at how Ellison had intended the episode to play out, as well as why producers deemed his version unfilmable—and the comic does the novelist’s legacy proud.

One of the most intriguing divergences involves Edith’s demise, for it’s the story’s villain who tries to save her, not its heroes. There’s a potential for good even in someone like Beckwith, while the honorable are capable, under the right circumstances, of allowing suffering and death to occur. Yet despite the man’s brief heroism, he is evil at heart, and he pays for his crimes in the end: when the Guardians return the Starfleet trio to their own era, Beckwith jumps back through the vortex to escape justice, only to gruesomely perish in an exploding sun.

Some (this writer included) consider the aired episode superior to Ellison’s intentions. After all, the script does not jibe with established Star Trek, and Spock comes off like an entirely different person. But whatever story flaws there may be, there’s intelligence and poetry in Ellison’s words, and the Tiptons and Woodward do an admirable job of bringing them to life. If one views the adaptation as an alternate reality in a vast multiverse, then there is much to appreciate.

Around the same time as the miniseries, IDW also released the Tiptons’ Star Trek Special: Flesh and Stone, illustrated by two other brothers, Joe and Rob Sharp. Flesh and Stone’s story is not complex, but what makes it special is that it featured main characters from The Original Series, The Animated Series, The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise, all in the same tale.

The premise: a paralytic virus disrupts a Starfleet medical conference at Diamandis I, crystalizing everyone aboard the space station. The Next Generation’s Beverly Crusher, along with Katherine Pulaski (Crusher’s season-two replacement) and Deep Space Nine’s Julian Bashir, assist Voyager’s Emergency Medical Hologram in battling the disease, despite their being unable to come aboard lest they, too, become infected. The trio seek assistance from Leonard McCoy, who looks oddly younger than he did in “Encounter at Farpoint” at age 137.

Now more than 150 years old, McCoy gets around via a wheelchair reminiscent of Christopher Pike’s in “The Menagerie” (though Bones is not confined to his). The scene includes an amusing nod to Star Trek: The Motion Picture, for he warns the doctors that they’d better not be there to draft him again. Flesh and Stone takes place in the 2380s, with McCoy enjoying retired life at an agricultural colony. WildStorm’s Star Trek Special had depicted Bones on his death bed at 144, but it’s not difficult to reconcile the two accounts—he simply bucked the odds and recovered. McCoy is unkillable.

A flashback shows Bones saving a trading post near the Tholian border (“The Tholian Web”) from the same virus, with help from Star Trek: Enterprise’s Phlox, as well as Joseph M’Benga from “A Private Little War” and “That Which Survives” (now a main character on Strange New Worlds). This makes Flesh and Stone a rarity, as it’s one of the only comics ever to feature an Enterprise cast member. What’s more, Arex appears in the flashback, representing the 1970s cartoon.

The outbreak had been caused by Federation personnel trading for Tholian silk, and this gives a radical Tholian splinter group the idea, a century later, of unleashing it on Diamandis I. The EMH exposes that scheme, earning the respect of Pulaski, who is said to have returned to her posting as chief medical officer of the USS Repulse (“The Child”) after leaving the Enterprise. As illustrated in that episode, as well as in “Where Silence Has Lease” and “Elementary, Dear Data,” crotchety Kate has harbored bigotry toward artificial life. Thus, her acknowledgment of the EMH as an equal provides satisfying closure to her onscreen arc.

This week’s column boldly brought us to an alternate timeline in which Ellison’s vision for his Star Trek masterpiece came to pass. Next time, we’ll continue that trend with a trip back to the Kelvin timeline in IDW’s ongoing comic based on J.J. Abrams’ films. This one features Q, time travel, and the Deep Space Nine cast, so don’t miss it.

Looking for more information about Star Trek comics? Check out these resources:

- My ongoing column for Titan Books’ Star Trek Explorer magazine

- The Complete Star Trek Comics Index, curated by yours truly

- The Star Trek Comics Checklist, by Mark Martinez

- The Wixiban Star Trek Collectables Portal, by Colin Merry

- New Life and New Civilizations: Exploring Star Trek Comics, by Joseph F. Berenato (Sequart, 2014)

- Star Trek: A Comics History, by Alan J. Porter (Hermes Press, 2009)

- The Star Trek Comics Weekly page on Facebook

Rich Handley has written, co-written, co-edited, or contributed to dozens of books, both fiction and non-fiction, about Planet of the Apes, Watchmen, Back to the Future, Star Trek, Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, Stargate, Dark Shadows, The X-Files, Twin Peaks, Red Dwarf, Blade Runner, Doctor Who, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Batman, the Joker, classic monsters, and more. He has also been a magazine writer and editor for nearly three decades. Rich edited Eaglemoss’s Star Trek Graphic Novel Collection, and he currently writes articles for Titan’s Star Trek Explorer magazine, as well as books for an as-yet-unannounced role-playing game. Learn more about Rich and his work at richhandley.com.

2 thoughts on “Star Trek Comics Weekly #108”